Peru ends the present century under the rampant authoritarianism of a president who rigorously applies the precepts of the most savage neoliberalism. The auto-coup that Alberto Fujimori (aka «El Chino» – the chinese) perpetrated in 1992 has allowed him, during the following eight years, a free hand to undertake all sorts of antisocial economic measures and to exert a ferocious repression against any inklings of radical political activism.

After this period the results, according to Human Rights organizations, have been more than 500 innocent people deprived of their freedom, accused of ties to the guerrillas by military tribunals whose only worry is to jail anyone in the opposition or simply suspected of being in it. This indiscriminate prosecution yields good results for «El Chino», leaving the once powerful armed organizations very weakened: The MRTA (Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amaru – Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement) doesn’t seem to have recovered from the blow at the Japanese Embassy in Lima while Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) finds itself divided ever since its top leader Abimael Guzman issued orders from prison to cease the fighting, probably after being physically and psychologically tortured. (Among the juiciest declarations by «comrade» Abimael it is worth mentioning this one: «Do not pay attention to the anarchist propaganda appearing in certain places»). Thus freed of encumbrances, Fujimori and his team dedicate themselves to the job of oppressing the population with all kinds of burdens through the SUNAT (sort of a local Treasury). It is common throughout the country to find a commercial establishment out of business, with large «closed» signs for failure to give a customer a sales receipt. The feared SUNAT’s motto is very especific: «Closer to you every day». El Chino still has one more subject to master: to soften the dictator image he enjoys internationally. To that end he recently ordered the withdrawl of military squads who since 1992 have occupied the roofs of the country’s universities with the goal of «erradicating subversion» on the part of the young students. A measure which, among many others, seeks only to attract foreign capital, which begins to take strong roots, notably with Spanish capital (Telefonica, BBV, Banco de Santander …) which, finding it impossible to compete in Europe, sinks its claws in these lands. It is a Latin American country whose people deal as best they can with the economic fluctuations and the mesianism of a president who, running roughshod over his own constitutional laws, pretends to run in a new election. Faced with such a somber panorama there are those who bet on fairer, more egalitarian organizational models.

ANARCHISM IN PERU

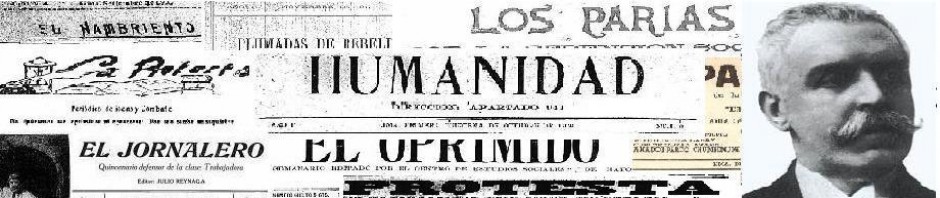

Towards 1870 there were already militants ranting against the state and capital in Peru, but it wasn’t until 1904 that the first decidedly organized groups appeared. That year the Union of Panaderos (Baker’s Union) was formed, with a clear anarchist influence, calling the first strike at the always combative port of El Callao. In 1906 the newspaper Humanidad appeared in Lima and in 1910 the Francisco Ferrer Racionalist Center published Paginas Libres (Free Pages). Three years later there was a general strike during the campaign for the eight-hour work day started by the Journeymen’s Union with important participation by anarchists through the groups «Luchadores por la Verdad» (Fighters for Truth), «Luz y Amor» (Light and Love) and the editors of the most important libertarian newspaper in Peru: La Protesta. This campaign achieved its objectives trade by trade until 1919 when, overrun by the development and magnitude of the struggle, the government was forced to establish the mandatory eight-hour work day throughout the country. The next step would be the creation of the Comittee for the Reduction of the Price of Staples, seeking reductions to the cost of basic commodities, transport and taxes, this struggle giving birth to the FORP (Federacion Obrera Regional Peruana – Peruvian Regional Federation of Workers) clearly anarchist, who would obtain important victories for the workers. Important militants of that time were Delfin Levano, Carlos Barba and Nicolas Gutarra among many. No doubt the most relevant figure and the most influential in workers’ circles would be Manuel Gonzalez Prada, still remembered by today’s activists. Gonzalez Prada edited, among other texts, Paginas Libres (Free Pages) (1894) and Horas de Lucha (Times of Struggle) (1908). During the early twenties a new organization guided by anarchists appears: The Union of Civil Construction Workers, publishing El Nivel (The Level) and El Obrero Constructor (The Construction Worker). During these years the non-stop workers’ activism suffered repressive response by the government. Printing presses were put out of comission, centers were closed and a good portion of the movement’s infrastructure with anarchist majority is destroyed, with the murder of many of its members. There was an uprising in the city of Trujillo, organized by anarchosyndicalist day workers, later co-opted by the APRA (Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana – American Popular Revolutionary Alliance), already formed as political party *. The workers’ movement, victimized by the repression and ruined by incipient political parties, lost its strength, with some survivors forming the Peruvian Anarchist Federation, where the libertarian ideal would remain alive, although in a more minoritarian fashion, publishing La Protesta during the next two years as well as documents about anarchosyndicalism in Peru until it disappeared in the sixties.

MODERN TIMES

Libertarian activity didn’t reappear until the end of the 80s, when some musical groups with certain political proclivities showed up in Lima. These were the first expressions of the so called «Underground Rock», a movement which shares many connotations with punk. As time went by these groups became more polarized with the musical aspect taking the back seat, ceasing to be an end to become only one of many possible means. At this time the guerrillas (MRTA and Sendero Luminoso) would recruit, thanks to better propaganda, infrastructure and preparation, many militants among the libertarian sympathizers of this movement. Antiterrorist laws in large measure limited the growth and development of these anarchist groups causing among them a certain self-limitation in order not to be identified with armed groups. In 1989 CAJA (Colectivo de Juventudes Autonomas – Autonomous Youth Collective) was created bringing together many from the so-called «underground movement» and which, without being openly anarchist (although with many anarchists within) would have an ephemeral life. At the beginning of the nineties new militants appeared who do not come from that musical base who, together with those who evolved from underground rock, create better defined groups, coming under the influence of libertarian propaganda from abroad, mainly from Spain. Autonomia Proletaria (Proletarian Autonomy) and Colectivizacion (Collectivization) appear in Lima, both still active at present. Autonomia Proletaria works in the anarchosyndicalist field, although it no longer believes anarchosyndicalism to be as effective a weapon as before. It works to spread the ideals among the workers with a publication which bears the same name, making commentaries about everything related to Peruvian and international syndicalist struggles. They changed their name in 1996.

Outside the capital and beginning at the north of the country we find libertarian representation in Piura with the collective Reconstruir (Reconstruct) and the publication El Inconforme, as well as fanzines and musical groups «underground». In Huanco ecological groups distribute alternative and libertarian material while in Huancayo Proyeccion Popular (Popular Projection) does its works and publishes the Reacciona (React) fanzine which has reached issue number 12. To the south, in Arequipa there is La Lucha (The Struggle) and the magazine Yaiyarguarta, which means «the blood of the people» in Quechua language, with some pages in this tongue, bringing to memory the work that the Federacion Obrera Regional Indigena del Peru (Peru Indigenous Workers Regional Federation) performed during the 20s and 30s, linking Peruvian anarchosyndicalism with the indigenous peasant movement in the southern part of the country. Also in Arequipa there are many musical groups and protest fanzines. In Cuzco, the ancient Inca capital, we find the MAP Movimiento Anarquista del Peru (Peruvian Anarchist Movement) in reality a small collective with a publication by the same name and which changed its name to El Obrero when its members began to feel under vigilance and qualified as «foreign elements» by the political apparatus. Colectivization publishes a magazine by the same name and links its activities to the university environment, makes historical and sociological balances regarding the current Peruvian situation, stating the libertarian ideal with renovating intentions. «Avancemos» (Let’s Advance) is yet another collective that tries to transcend the musical aspect that still surrounds some of the sympatizers, bringing the debate to a more political terrain. They organize concerts, talks, debates and other acts whose proceeds revert to the organizing of new activities. A while later Avancemos became the Coordinadora Sonidos the Accion (Sounds of Action Coordinator), a groups that aims to be the nucleus of a movement which, in autonomous fashion, will extend throughout the different neighborhoods of Lima and other cities. The Coordinadora prints Barricada (Barricade) and Despierta (Wake up). Other collectives are «Cambio Radical» (Radical Change) active in the northern area of the city and the group Ikaria which proclaims a «nihilist» anarchism. There is a great number of fanzines (Buscando un Camino – Searching for the Road, Cultura – Culture, and a long etc.) and musical groups which sympathize with the ideals, among the last Autonomia (Autonomy), Generacion Perdida (Lost Generation), Al Margen de la Ley (Outside the Law) and Los Recios (The Strong Ones). Restless university students organize talks about the Labor Movement, Gonzalez Prada and other topics with participation of libertarian comrades. There are also sympathizers among the animal rights activists who periodically organize campaigns against bullfights and for animal liberation. It is not strange that all this activity in Lima is being done by militants who multiply themselves among the various collectives so we can not speak of a very large number of militants. A big amalgam of groups and publications which try to coordinate and achieve greater efficiency but which face not a few obstacles. Fujimori’s coup in 1992 forced the Peruvian comrades to take precautions. According to Peruvian repressive laws, anarchists are classified as «independent terrorists» since they don’t fit under the typical «terrorism» – something which can bring hard prison sentences. Thus, local libertarians are forced to change meeting places, to be discreet when talking anarchism, change the names of their publications when they think they are being detected and other measures in that direction. Another serious problem is the lack of meeting places, being forced to gather in public and so getting undesired attention. More recently they have suffered from the overtures of the until recently marxist-leninist-maoist element with the goal of obtaining political advantage out of their labor and the libertarian ideals in general. In spite of the obvious difficulties, the Peruvian comrades are optimistic about their work and hope to advance the ideals they consider more just.

Address for anarchist contacts in Peru:

Ediciones Musicales – Aptdo. C. 330062 Lima (Peru)

Note:

* The APRA was characterized at that time by their taking advantage of Gonzalez Prada’s image as well as of anarchist ideas in their discourse, acting as a «degenerative» agent in the worker’s movement. In more recent times they have performed outrageous acts of corruption (as under the APRA government of Alan Garcia) and today some of its members collaborate in the Fujimori government.

link: http://www.ecn.org/communitas/en/en133.html