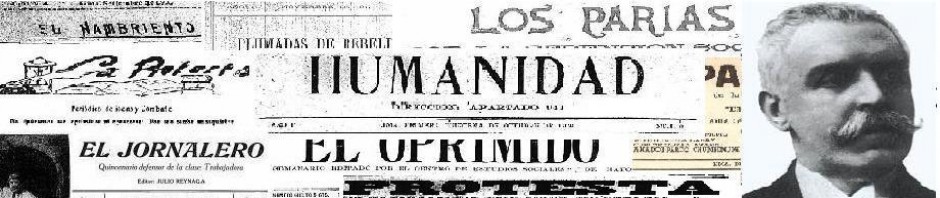

Jose Manuel de los Reyes González de Prada y Ulloa (b. Lima, Jan. 6 1844 – d. Lima, Jul 22,1918) was a Peruvian politician and anarchist, literary critic and director of the National Library of Peru. He is well remembered as a social critic who helped develop Peruvian intellectual thought in the early twentieth century, as well as academic style known as modernismo.

Contents

- 1 Early life and literary contributions

- 2 The Question of Sources

- 3 Politics

- 4 Quotes by Gonzalez Prada

- 5 References

- 6 Secondary bibliography

- 7 External links

Early life and literary contributions

He was born on January 6, 1844 in Lima to a wealthy, conservative, Spanish family. His education began at the English school in Valparaiso, continued in a seminary, and once his father refused to let him travel to Europe, he enrolled at the University of San Marcos in Lima, studying law. He was an original partner in the Lima Literary Club and he participated in the foundation of the Peruvian Literary Circle, a vehicle to propose a Literature based on science and the future. His most famous book, Free Pages, caused a public outcry that brought González Prada dangerously close to excommunication from the Catholic Church. His mother, a devout Catholic, died in 1888 and his criticism became more vitriolic afterwards. He said the Church «preached the sermon on the mount and practiced the morals of Judas.» In fact González Prada was part of a group of social reformers that included Ricardo Palma, Juana Manuela Gorriti, Clorinda Matto de Turner and Mercedes Cabello de Carbonera. These important authors were concerned with the enduring influence of Spanish colonialism in Peru. González Prada was perhaps the most radical of them all. The most radical work he published during his life time was Hours of Battle, translated as Hard Times.

Besides being a minor philosopher and a significant political agitator, González Prada is important as the first Latin American author to write in a style known as modernismo (modernista in Spanish, different from Anglo-American modernism) poet in Peru, anticipating some of the literary innovations that Rubén Darío would shortly bring to the entire Hispanic world. He also introduced new devices such as the triolet, rondel and Malayan pantun which revitalized Spanish verse. Besides his poetry, he cultivated the essay, and most recently Isabelle Tauzin Castellanos has published some of his hitherto unknown fiction. His intellectual and stylistic footprint can be found in the writing of Clorinda Matto de Turner, Mercedes Cabello de Carbonera, José Santos Chocano, Aurora Cáceres, César Vallejo, José Carlos Mariátegui and Mario Vargas Llosa.

The Question of Sources

To talk about González Prada’s sources and influences would be to write an encyclopedia of European and Latin American thought during his life time. Suffice to say that some of his major influences were Auguste Comte, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Ludwig Gumplowicz, Ernest Renan, Juan Montalvo, Clorinda Matto de Turner, Mikhail Bakunin and many, many others. One way to put it—and perhaps oversimplify it—is to say that González Prada was first a positivist following Auguste Comte, but that later in life, as he took up the working class’s cause and anarchism, he came closer and closer to thinkers such as Renan, Proudhon and Bakunin.

Politics

He was a member of the Civilista Party but left to found with his friends, a radical party known as the National Union, a party of «propaganda and attack.» This party named him as a presidential candidate, but he fled to Europe following persecution. After the War of the Pacific, he returned to Peru in 1898. He stood as his party’s Presidential Candidate in the Presidential election of 1899 and came third with 0.95% of the vote. After Peru’s defeat in the War of the Pacific, he stayed in house for three years, refusing to look at the foreign invaders.

After his failure in the Presidential election he was asked to work for the newly formed government. He took up the post of director of the National Library of Peru, in the Abancay Avenue and helped to improve and reorganise the library to one of international stature. He died of a cardiac arrest on the 22nd of July 1918.

Although he didn’t consider himself a Communist, Gonzalez Prada was close to Marx in economic theory. He opposed the Russian Revolution in 1917 and rejected the rigidity of the Communist party. He criticized the aristocratic class (of which he was a member) for its crimes and its wasting opportunity. Gonzalez Prada called on workers, students and Indians to take over reform Peru.

Quotes by Gonzalez Prada

on Peru:»We have never initiated a reform, never announced a scientific truth, nor produced an immortal book. We do not have men but mere echoes of men, we do not express ideas but repetitions of decrepit and moth-eaten phrases.»

On Revolution: «Revolutions come from above but are carried out from below. Their way lighted by the gleam on the surface, those who are oppressed in the depths see justice clearly and thrust forward to conquer it, without hesitating as to the means nor feeling fear as to the consequences. While the moderates and theoreticians imagine geometric evolutions or get all tangled up in the details of form, the multitude simplifies matters, taking them down from the nebulous heights and confining them to earthly practice. They follow the example of Alexander; they do not untie but cut the knot which binds them.»

On Liberty: believed «that all liberty was born bathed in blood…Rights and freedom are never granted; they must be taken. Those who command give only what they must, and nations which sleep trusting their rulers to arouse them with the gift of liberty are like fools who build a city in the midst of a desert hoping that a river will suddenly flow through its barren streets.»

References

- González Prada, Free Pages and Hard Times: Anarchist Musings. Oxford University Press (2003). ISBN 0-19-511687-9 (hardcover) and ISBN 0-19-511688-7 (paperback).Secondary bibliography

Secondary bibliography

- Rufino Blanco Fombona, Grandes escritores de América, Madrid, 1917.

- Eugenio Chang-Rodríguez, La literatura política: De González Prada, Mariátegui y Haya de la Torre, Mexico, 1957, esp. pp. 51-125.

- John A. Crow, «The Epic of Latin America,» Fourth Edition, pp. 636-639.

- Joël Delhom, «Ambiguités de la question raciale dans les essais de Manuel González Prada», en Les noirs et le discours identitaire latinoaméricain, Perpignan, 1997: 13-39.

- Efraín Kristal, Una visión urbana de los Andes: génesis y desarrollo del indigenismo en el Perú, 1848-1930, Lima, 1991.

- Robert G. Mead, Jr., Perspectivas interamericanas: literatura y libertad, New York, 1967, esp. pp. 103-184.

- Luis Alberto Sánchez, Nuestras vidas son los ríos…historia y leyenda de los González Prada, Lima, 1977.

- Isabelle Tauzin-Castellanos, ed., Manuel González Prada: escritor de dos mundos, Lima, 2006.

- Marcel Velázquez Castro, Las máscaras de la representación: el sujeto esclavista y las rutas del racismo en el Perú (1775-1895), Lima, 2005, esp. pp. 249-264.

- Thomas Ward, La anarquía inmanentista de Manuel González Prada. New York, 1998.

- Thomas Ward, “González Prada, la mente y las manos”. Revista Peruana de Filosofía Aplicada, año 9, núm. 11 (1999): 46-54.

- Thomas Ward. “González Prada: soñador indigenista de la nación”, en su Resistencia cultural: La nación en el ensayo de las Américas, Lima, 2004: 160-177.

Link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manuel_Gonz%C3%A1lez_Prada